A recent report published by Intrepid suggesting travel is hovering on the “brink of extinction” could be interpreted by some as a cynical attempt to jostle the industry into action on climate change by evoking fear.

However, outside of the anxiety-inducing language involved, the study did in fact raise several constructive propositions as to how the industry might reform itself in the fight to lower its overall carbon impact.

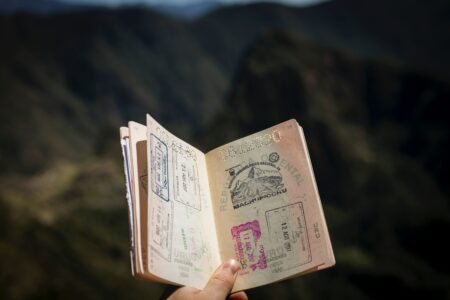

One forecast that really caught my eye was the notion of a carbon passport, which in the report was suggested as a necessary tool the world will be forced to adopt once we reach the “tipping point” on global warming.

I must confess I first heard the concept of limiting travel using a carbon baseline in dispatches during the ‘flight shame’ movement popularised by climate activist Greta Thunberg in 2018.

Amongst the marauding masses of well-intentioned activists flipping over luggage at airports in Europe and brandishing placards pillorying the aviation industry, there were, mercifully, a few rare exceptions in the rabid throng prepared to be more practical about how to balance the moral imperative of climate action with the realities of commercial travel.

While most seemingly chanted for a shutdown of aviation altogether, a minority were more interested in coming up with tougher policy measures needed to cajole travellers and airlines alike into action.

One such suggestion bandied about informally at the time was the idea of limiting travel based on carbon emissions.

Put simply, a carbon passport as conceived of in Intrepid’s report would effectively look to cap how many kilometres a traveller could fly during a given year in a bid to force the hand of individuals who are currently not prepared to book greener alternatives to flying where possible.

The move, depending on how extreme its application, could for example potentially limit one’s ability to fly from deep in the Southern Hemisphere to Nordic countries like Finland for fear of maxing out a yearly travel allocation.

While most agree this specific conception of a carbon passport is highly unlikely to be introduced anytime soon, the fact is with climate change already demonstrably impacting the lives of millions around the world, action by governments will inevitably be called upon to intervene more and more as time goes by to mitigate the looming environmental apocalypse.

My issue with the flight shame movement has been, broadly speaking, the narrow field of scope in which its participants view the problem of aircraft emissions.

It seems to me that merely attaching a stigma to a behaviour in order to stop it is both unrealistic and, perhaps most crucially, unlikely to affect any credible change in consumer behaviour.

The thinking is akin to those conservatives out there who feel the only way to stop the scourge of drug addiction is to make drugs illegal.

Problem solved, apparently.

No, like most complex issues it requires a multifaceted approach that prioritises at its heart, good incentives.

To be real for a moment, aviation is neither the sole, nor even the biggest contributor to global emissions – that unwanted mantle goes to energy production and agriculture.

It would probably make more sense for climate activists to be picketing consumers lining up to buy their latest Apple smart devices and those purchasing meat at the local butcher than trying to shut down airports.

But of course, protests are always about more than just the data. They seek to seize headlines and make a splash, and as tempting as it might be for the more caustic activists to shove seniors around at the local deli, the larger swathe of attention is there to be grabbed at the top end of town.

If you want to make some noise about animal rights, protesters are likelier to be found at the entrance of the Melbourne Cup gates than traipsing through acres of a remote factory farmland.

You catch my drift.

While proportionality is clearly important in forming policy, it’s also my view that at all levels of society it is incumbent on good global citizens to do their best to look after the planet for future generations.

So, what to do?

This is where my interest was recently piqued about the carbon passport.

The report commissioned by Intrepid and compiled by The Future Laboratory suggested that personal carbon emission limits will become “the new normal” in the future as people’s values drive an era of great change.

“On our current trajectory, we can expect a pushback against the frequency with which individuals can travel, with carbon passports set to change the tourism landscape,” the report contends.

“By 2040, we can expect to see limitations imposed on the amount of travel that is permitted each year.”

When I read this, I must admit a gnawing sense of contradiction was difficult to shake off.

If people’s values were expected to be the driver of positive change, why would we then need such a blunt instrument approach that would place hard limits on how far a person can travel?

Which is it? Will good intentions displayed by an ever-more-enlightened population be the change agent in lowering the carbon footprint of travel, or will it need to be forcibly stamped out by a strict carbon passport?

In any case, I would make the argument that such a passport need not be so punitive, but rather could form the foundation for a raft of positive incentives put forward by travel companies in lockstep with governments for travellers to rein in their carbon spend.

While the report was less clear about how a carbon passport might work in practice, when I contacted Intrepid for clarity, I found their view on the concept far more compelling.

It’s also important to bear in mind that this is an operator noted for far more than rhetoric, and on this issue Intrepid has already introduced carbon labelling on more than 500 of its itineraries.

Global Environmental Impact Manager at Intrepid Travel, Dr Susanne Etti, explained to me that informed decision-making would be at the epicentre of any successful carbon passport scheme.

“A carbon passport will serve as a transparent record of an individual’s carbon emissions, fostering an environment where consumers can make more informed and sustainable choices,” she argued.

“The concept of a carbon passport is set to evolve further with the integration of AI, enabling travellers to log their daily emissions and monitor travel metrics in real-time, empowering them to reduce their carbon footprint actively and meet personalised carbon reduction goals”.

Enabling more informed choice for travellers certainly makes more sense if the ultimate goal is to change the hearts and minds of travellers about how their holiday plans might impact the planet.

But as I alluded to earlier, a system of positive incentives is also fundamental to affecting long-term change.

In a way I’m making a somewhat wretched indictment on humankind, and as much as it pains me to admit this, people on the whole are typically motivated by immediate and short-term fulfilment over loftier moral ideals like preserving the planet from pollution.

I take no pleasure in being the bearer of this grim opinion, but the reason people like Greta Thunberg and David Attenborough are famous for their conservation efforts is because there simply aren’t too many Thunbergs and Attenboroughs who have dedicated their entire existence to raising the profile of important environmentalist causes.

Sure, there are plenty of impostors who masquerade as activists by being a one-issue candidate before heading home to juice up tonnes of carbon on Instagram and buying and selling crypto online.

But the true eco warriors I surmise are few and far between.

So, in this light for any carbon passport scheme to be successful, it will need to act as a bank account to encourage people to make good and moral decisions.

In exchange for travelling fewer kilometres and with a lower carbon impact, the question of ‘what am I getting in return’ will need to be answered by the industry with gusto.

Travellers will need to be offered bonuses, cashbacks, discounts, access to perks, to name just a few, as rewards for making greener travel decisions.

This seems to me far more likely to be effective in changing habits than pinning our collective hopes to a critical mass of people waking up one day and wanting to make better choices for the globe.

If the economic incentives are geared towards making the shift to take fewer business trips, stay in hotels with green certifications, take more trains over planes, book tours with companies with a scrupulous sustainability record etc, then we had better start appealing to far more than people’s consciences and start courting their wallets as well.

A carbon passport where all of these types of rewards can be stored and tracked by good commercial actors in travel sounds like a concept we should be working on creating today, instead of hitting the big red button in 2040.