ONE of the inspiring qualities I’ve observed about people working in travel is their unfettered curiosity. I know it shouldn’t be surprising given the gig literally involves championing the exploration of the world, but this wonderful spirit of enquiry is in my view a virtue rapidly vanishing from public view.

Too often people fester away in their echo chambers online, over time adopting increasingly narrow vantage points in which to authentically understand the world around them. The pernicious digital architecture that big tech has assembled for us has the uncanny knack of amputating people’s ability to appreciate alternative opinions and cultural perspectives, and it is in this polarising climate that travel represents perhaps one of the most promising inoculants to this concerning trend.

An increasing number of operators are pushing the boundaries of interconnectivity, ensuring travellers are having more immersive and culturally nourishing experiences than ever before. The diverse range of travel products currently on offer, both in terms of destination and nuanced activities, is testament to the healthy shift away from the formulaic flop-and-drop holidays that once dominated the market. However, in this pursuit of finding new cultural horizons and expanding to new markets, the insatiable quest for the ‘new’ and ‘intriguing’ has brought with it plenty of moral tension.

This has been especially evident when examining the emergence of oil-rich nations in the Middle East like Qatar and Saudi Arabia, with each nation throwing unprecedented amounts of money at making themselves an attractive tourist destination in preparation for life after fossil fuel demand, while at the same time continuing to enforce the type of archaic rules on women and the LGBTQI community that we in Australia would find unconscionable. The collision of moral norms that has accompanied this investment has left plenty of people questioning whether it is ethically justifiable to pour money into the coffers of countries with dubious track records on human rights.

For me, the answer to the ethical conundrum lies in the rejection of the same zero-sum thinking I alluded to earlier. The question should not be, ‘should we travel or not travel to certain countries’, but rather ‘what is the most morally responsible way to conduct trips to nations that possess wildly different mores than we do’?

Intrepid’s purpose-driven model is one example of how to navigate these tricky waters successfully. The company recently launched female-only tours of Pakistan for 2023, a country rife with physical and economic abuse of women, with tours taking travellers to support businesses and local industries that Pakistani women rely upon to live a safe and financially independent life. In this way we can see it is possible for travel to form part of the solution to social problems and not simply contribute to troubling status quos that support the cycle of inequities and abuse.

It is also worth drawing a philosophical distinction between travel supporting the residents of a country versus the abusive regimes that often oppress them. In this light it can be argued the moral imperative is for the travel sector to unearth innovative ways to support the economic plight of disadvantaged people living under these austere governments and not simply bury our collective heads in the sand and pretend such problems don’t exist. There is no doubt in my mind that travel has the ability to play an important role in bringing the struggles of oppressed communities to light, and, ideally, affect some form of positive social change. What better way to foster this empathy than to take a trip and see these lives being lived in the flesh, listen to the stories of locals, eat a meal with their families and walk a day in their shoes?

This is the true power of travel, it’s ability to break down the barrier between reality and perception.

Having said all of this, I am cautious not to wax lyrical too much about how the growth in tourism around the world will inevitably lead to positive regime change and universal social reforms, because the truth is it remains unclear to me if that is indeed an accurate summary of the facts. In Saudi Arabia for example, we hear and read a lot in the mainstream media about how the country is modernising and making reforms in a bid to become a more palatable place for visitors, many pointing to the repealing of a ban on women to drive as proof there is a moral metamorphosis underway. But the reality is that one concession sits in the foreground of a country that has arguably gone backwards on human rights under the strict leadership of Mohammed bin Salman. So perhaps the cautionary tale here is for travel businesses to have their guards up against self-interested narratives propagated by questionable governments, and instead focus on what progress can be made on the ground in the country’s most vulnerable communities.

So, to those who say there are countries in the world that we simply should not visit, I respectfully disagree.

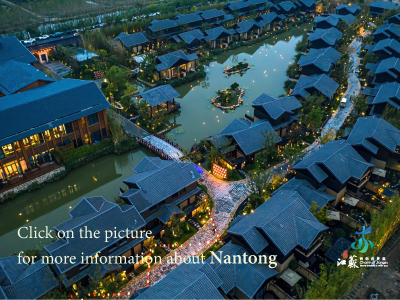

‘Cancelling’ countries will not make the world a better place or improve the lives of marginalised groups, in fact, disengaging economically from these types of nations tend to hurt the people sitting at the bottom of the pile the most. Should we abandon the opportunity to visit the beauty of China because of the government’s deplorable treatment of its ethnic minority Uyghur population? I respectfully think the answer is no. People should be able to take awe-inspiring trips of the Red Dragon without feeling as though they are giving tacit endorsement to the regime’s ideological view.

Empowering local communities through constructive visitation may just be one of the important levers to incrementally improve the situation. Most travellers are curious by nature, they want to expand their horizons and experience the world in more vibrant colours than they have before, and for people working in the travel sector, the mission should be to light the way and show people the most ethical way of doing just that – not serve as rigid gatekeepers and eliminate entire markets. It’s often said that charity begins at home, well, perhaps it should end with a trip as far away from the home as possible.